In Samarkand, I stayed at a charming family-run guesthouse (TOP TIP: the Antica Family Guesthouse – don’t tell a soul about this place, I want to keep it a secret, just for me) a stone’s throw from Tamarlane’s mausoleum. Behind a stout, ornately-carved gateway, the rooms are comfortable, tasteful and decorated with local crafts, the breakfasts are a slice of local home-cooked cuisine, delicious at that, there is a gorgeous central courtyard with a lush garden and the whole place is run by four generations of women from the same family.

We met Emir Timur in Uzbekistan – The Silk Road: Tashkent. Who knows, the missing horse todger may have even ended up here, in Samarkand. During a break in the work, when Russian archaeologists decided to open up the tombs of Tamerlane and his descendants in 1941, some local elders came to the photographer for the expedition, one Malik Kuyumov, and told him about the curse. Kuyamov took them to the dig leaders and they showed the Russians a seventeenth-century book. In this was written:

‘Whoever disturbs Timur’s tomb will release a spirit of war. And such a bloody and terrible slaughter will commence that the world has not seen in all eternity!’

Inside the tomb, inscribed on the coffin were the words:

‘Whoever opens my tomb shall unleash an invader more terrible than I.’

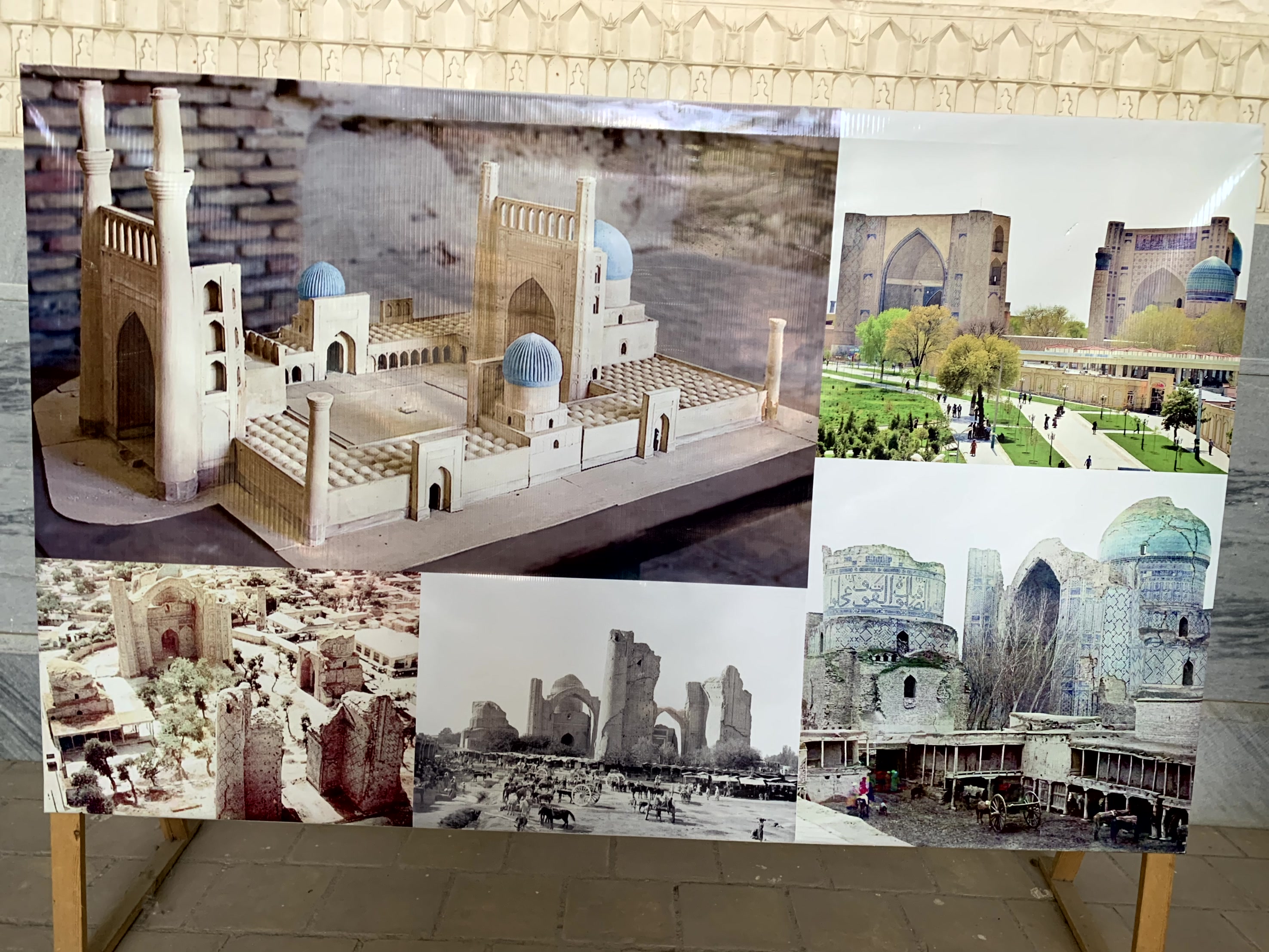

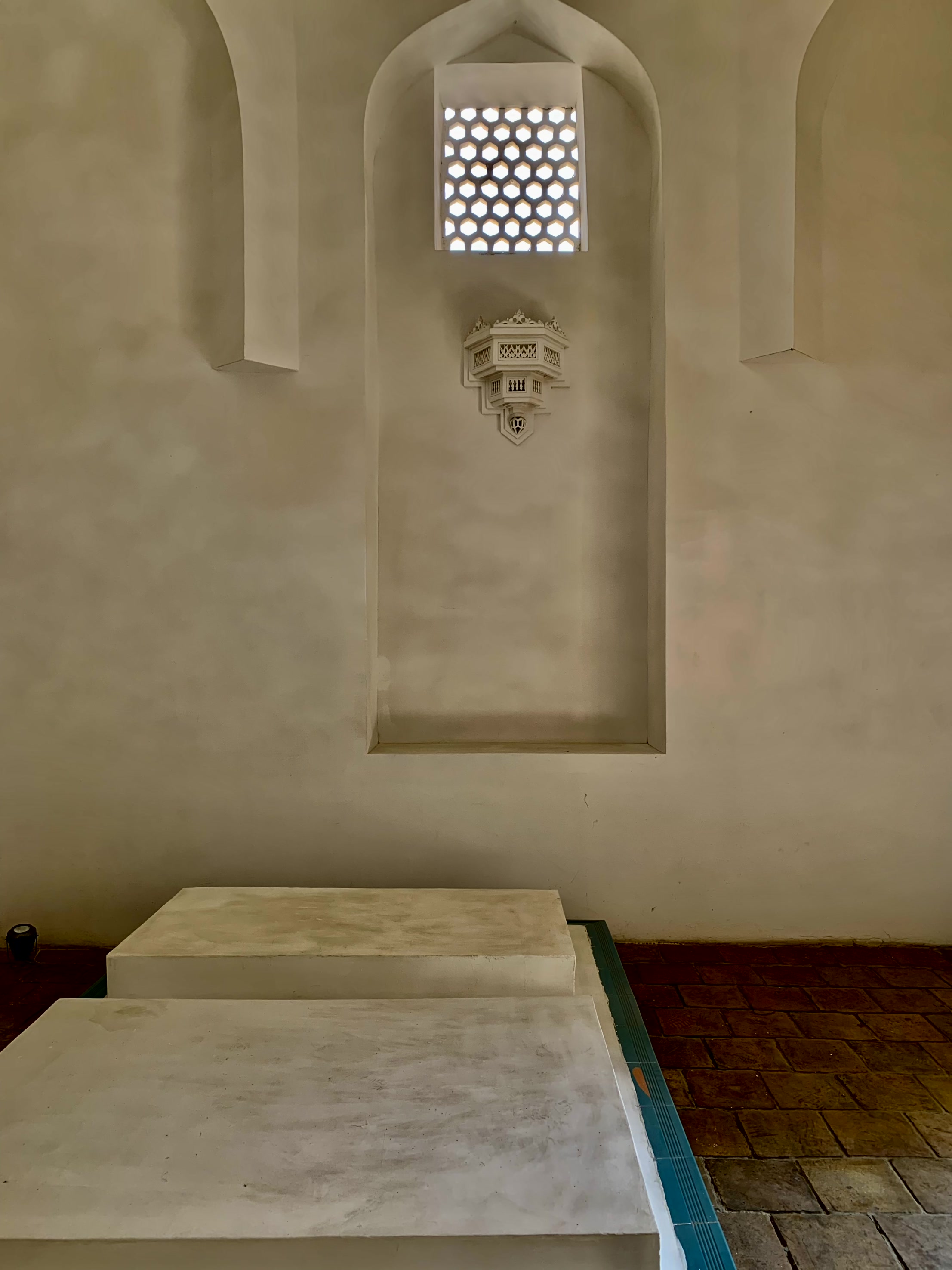

The day after the tomb had been opened, on 22nd June 1941, Nazi Germany invaded Russia. Tamerlane’s remains were taken for study to Moscow. While they were in Moscow, the anthropologist/sculptor Mikhail Gerasimov managed to reveal what Tamerlane looked like and even sculpted a portrait. This is the basis of the many statues and portraits you see around Uzbekistan today. He was above average height for the epoch, had Mongoloid features, red hair and a wedge-shaped beard (Timur that is, not Gerasimov). Gerasimov also found evidence that the medieval leader had an injury to his right arm and leg sustained during his twenties and the remains told of an individual of great physical strength. His grandson, the famed astronomer Ulugbek, had died from being beheaded. Ulugbek had set up an observatory and drew up astronomical tables of astonishing accuracy that predicted eclipses and the like in a time 200 years before the invention of the telescope. His observatory was built in 1429 and Ulugbek could subsequently calculate the precise times of the rising sun, measure the length of the year and determine the tilt of the earth. In 1449, Ulugbeks’s observatory was destroyed by religious fanatics.

When Stalin heard about all this, he ordered the remains to be put back in their rightful place where they were buried according to Muslim traditions. This occurred on the 19-20th November 1942, the very days that a crucial battle was fought around Stalingrad – a counter-attack that was a key point in turning the war back in the Russian’s favour.

I visited the Registan, an eye-popping ensemble of madrasas and mosques dripping with majolica and entrances soaring high above the visitors. As I was leaving, I was greeted by the bizarre sight of what seemed to be a would-be boy band dancing in front of the complex to a loud Asian style of pop from a speaker and being filmed for a reason that I know not.

I walked out to the Afrosiyob museum, situated on the site of the oldest part of Samarkand, now little more than scrubland concealing mostly still-unexcavated wonders just outside the city. It was annihilated when Genghis Khan passed this way but had trading links throughout Asia and Europe from antiquity. Here they have found artifacts from ceramics from the fourth century BCE to ancient Greek coins, juniper wood beams, weapons and murals from a great palace dating back to the seventh century CE. The frescoes show the Sogdian king Varkhuman, the Chinese Tang Emporer Gaozona and Zoroastrians from Iran and Mongolia. The usual Silk Road suspects. A few km further is the remains of Ulugbek’s observatory. All that is left now is the track from the 40m radius sextant and there’s a museum with models to show what it would all have looked like back in the day.

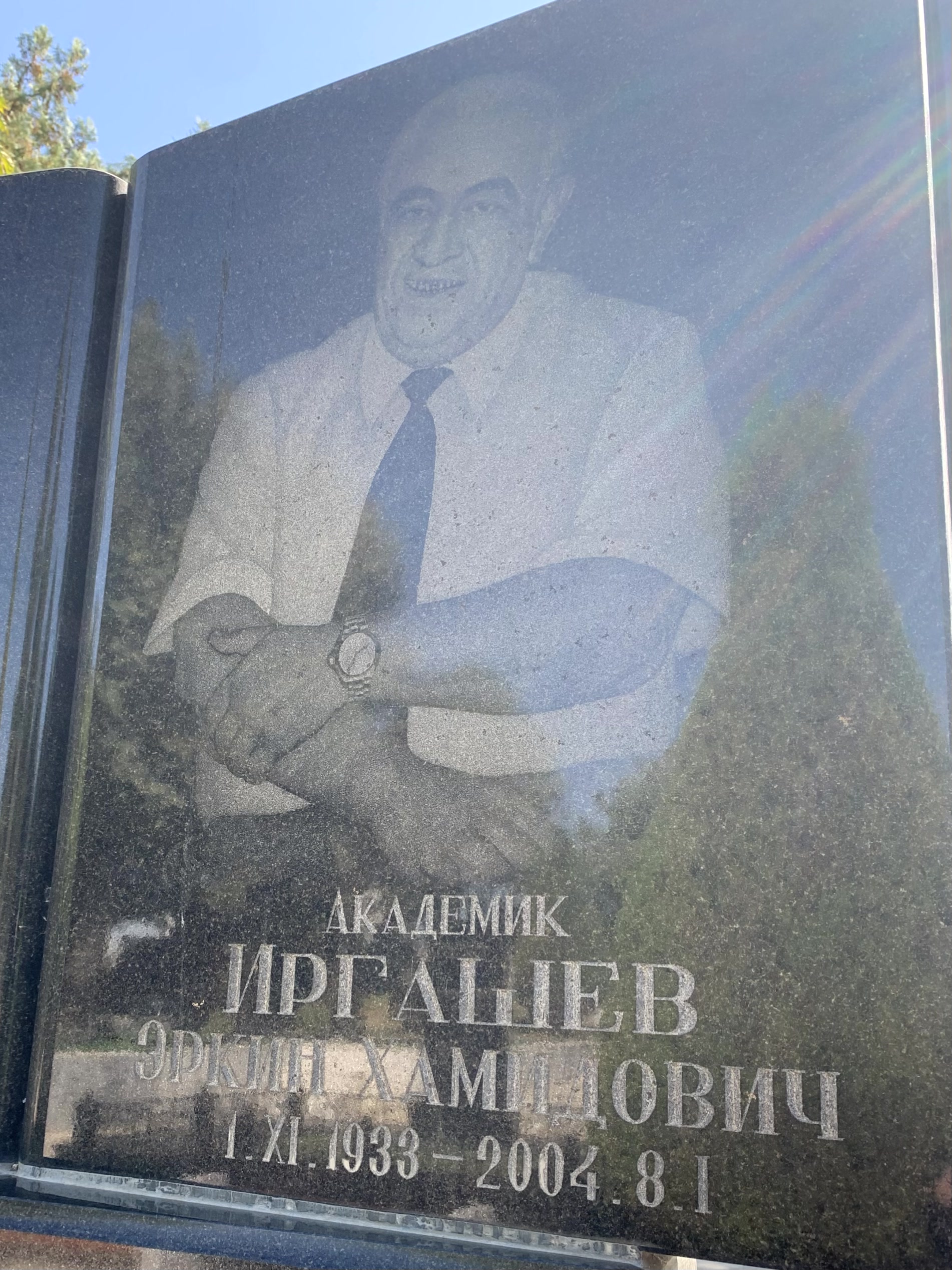

On the way back from this long hike out of town, I stop off to look around the Jewish and then the Muslim cemeteries. It was quite an amazing experience on that hot afternoon. The gravestones are of black marble and etched into each is a photograph of the deceased. Somehow these have been fused into the shiny stone, pictures of people wearing their best clothes, most men wearing ties and suits. The result is that you feel connected in some way to these images and to these people. It was like standing in a crowd, wandering around all alone in those cemeteries. A couple had been musicians and held their instruments. One was backed by stars and held astronomical instruments, people whose faces showed kindness or wisdom. It was hot and I stopped for a while to rest by one woman with a notably kind look in her face. I felt the pain of parents before the images of infants, admired rows of medals and wondered what they were for and about their bravery. Seeing their faces somehow enabled a connection to their past lives from a traveller from a different time and place. It wasn’t spooky, more of a reverential experience. I suppose the poignancy was enhanced by meeting these people alone.

The old Jewish quarter has been cordoned off by an ugly fence and the only way in from the main drag is through a small gate beside the tourist office. But it’s a peaceful place to wander around for a break from the trinket stalls that line the streets and have taken over the madrasas.

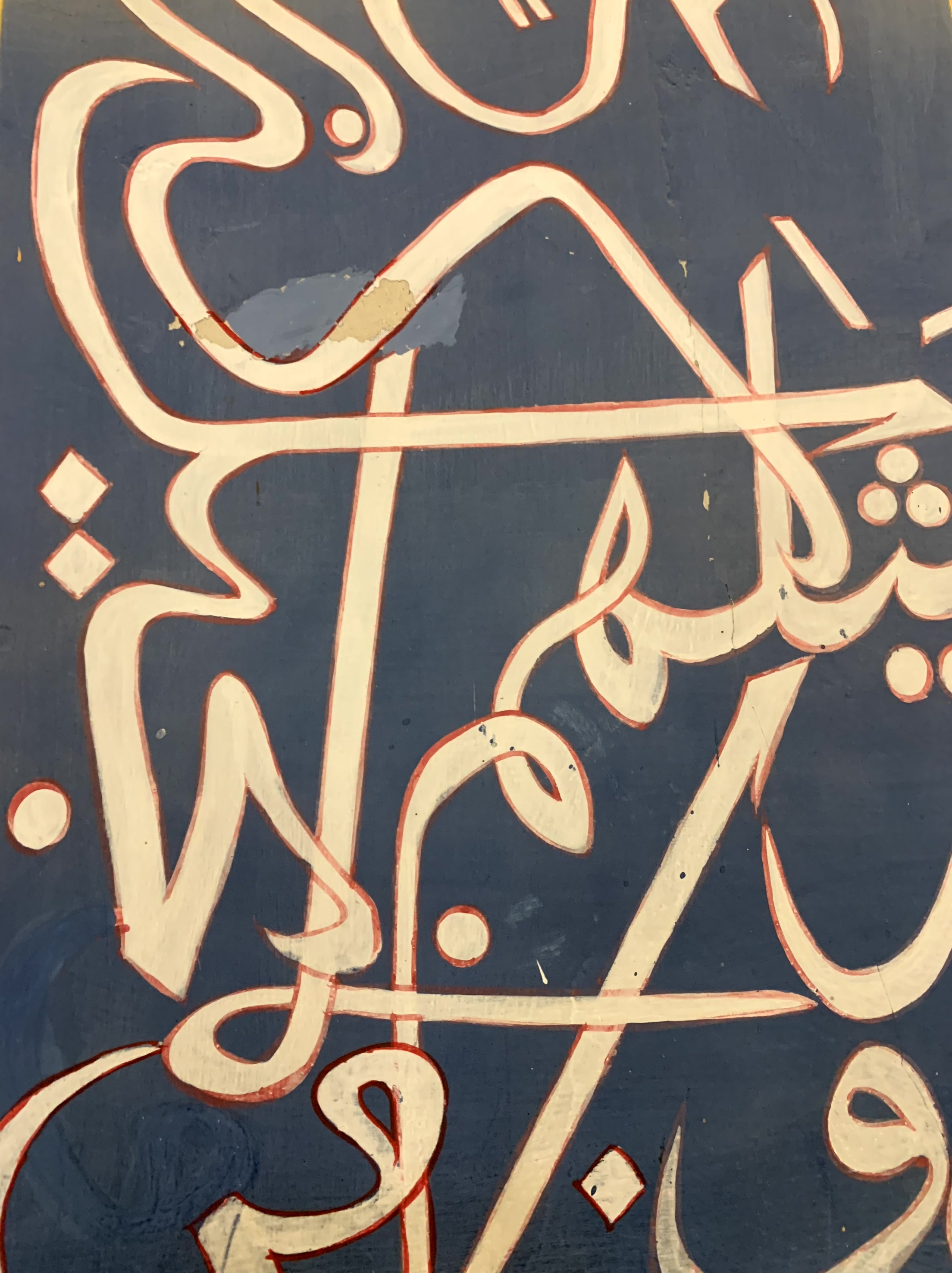

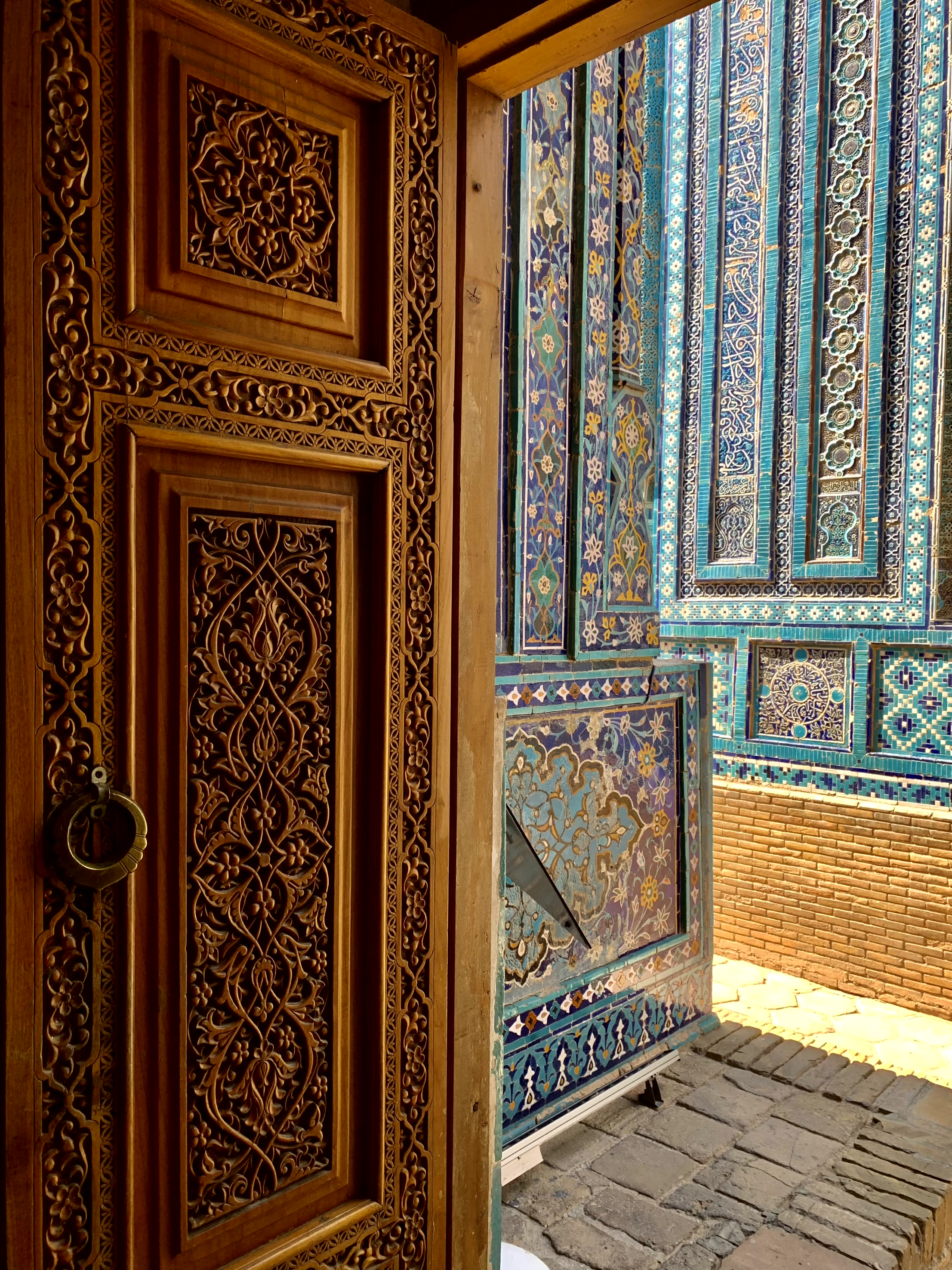

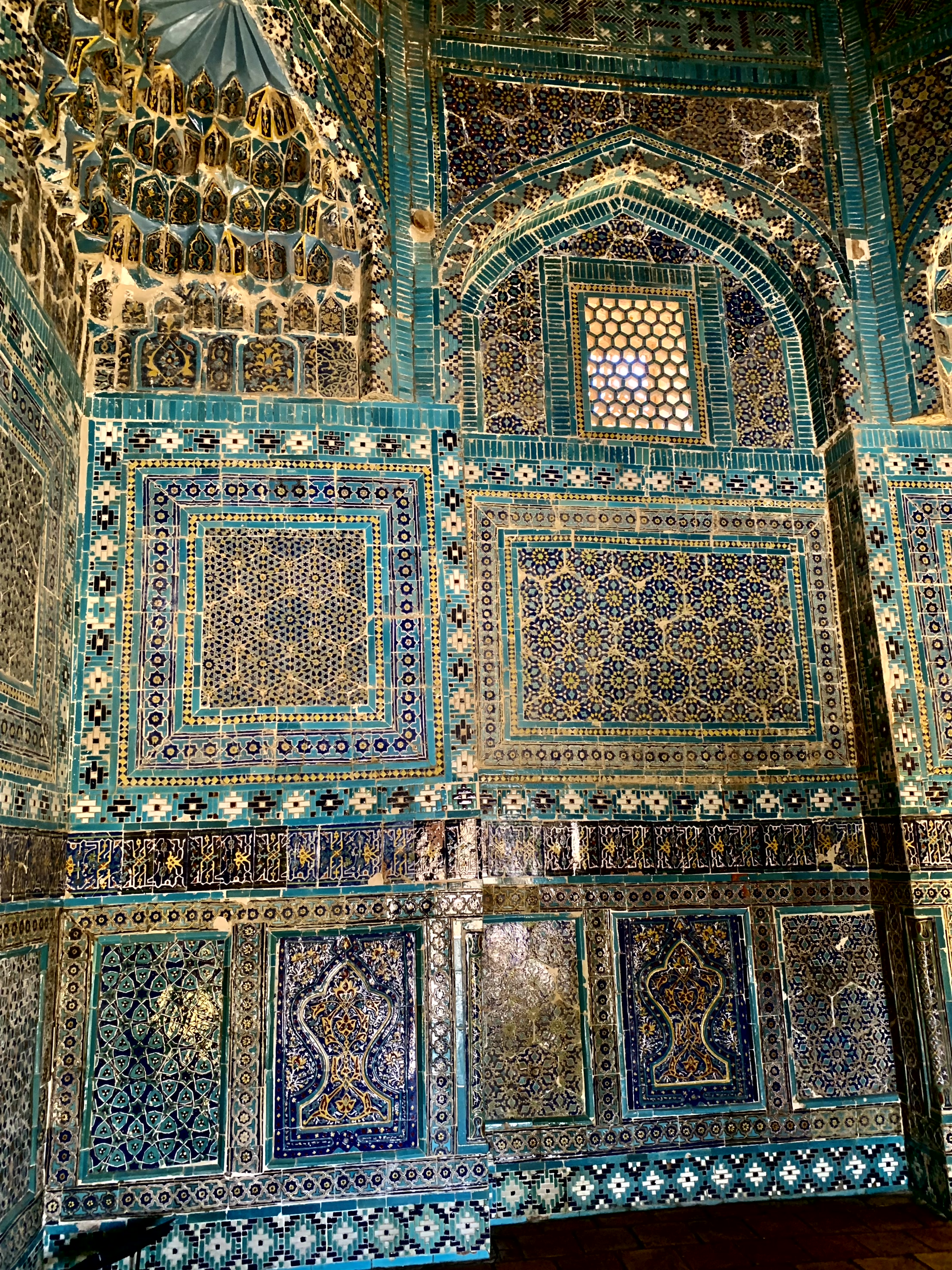

Shah-I-Zinda, lying between the cemeteries and the centre of town, is a whole avenue of mausoleums of the great and the good from the courts at around the time of Emir Timur (14th to 15th centuries CE). It is said to contain some of the richest tilework in the Muslim world. And I wouldn’t disagree. I also took a walk around the Russian town, with its well-kept parks, orthodox church and bustle of daily Samarkand doings.

Samarkand, and especially its ancient sites, has been described by the word ‘Disneyfied’. It is true that the main historical sites have been greatly restored and house tourist shops, but it’s not quite fully there yet. The Jewish quarter is an example. Some of the charming, crumbling buildings here already have government plaques on them marking them as points of historical interest but the tourists have not got there yet (apart from a couple of small family hotels) and Afrosiyob, the cemeteries and the observatory are far enough out of town to be quieter. Nevertheless, apart from being right up there with epic romance-of-travel place names like Timbuktu or Zanzibar, Samarkand is a belter of a place to visit.

Will you let me have a free pee if I sort out that upside down ‘m’? It’s not WC for women and MC for men…

A fantastic write up! I need to get my butt into gear and write some more about my Uzbekistan trip last month!

LikeLike