My final stay in Uzbekistan was in Bukhara, another fabled Silk Road city. Fahoot, the son of the owner of the hotel, met me from the bullet train from Samarkand and had excellent English gained from his time as an agricultural worker in Hereford. He used to get to work a quarter of an hour before the six o’clock start, he told me, whatever the weather, whereas others turned up late and he’d been asked to come back this year. But, he told me, the ‘easy’ life he enjoyed working for his Dad, plus his vending machine business in hospitals, as well as having a young family meant that he prefers to stay here for now.

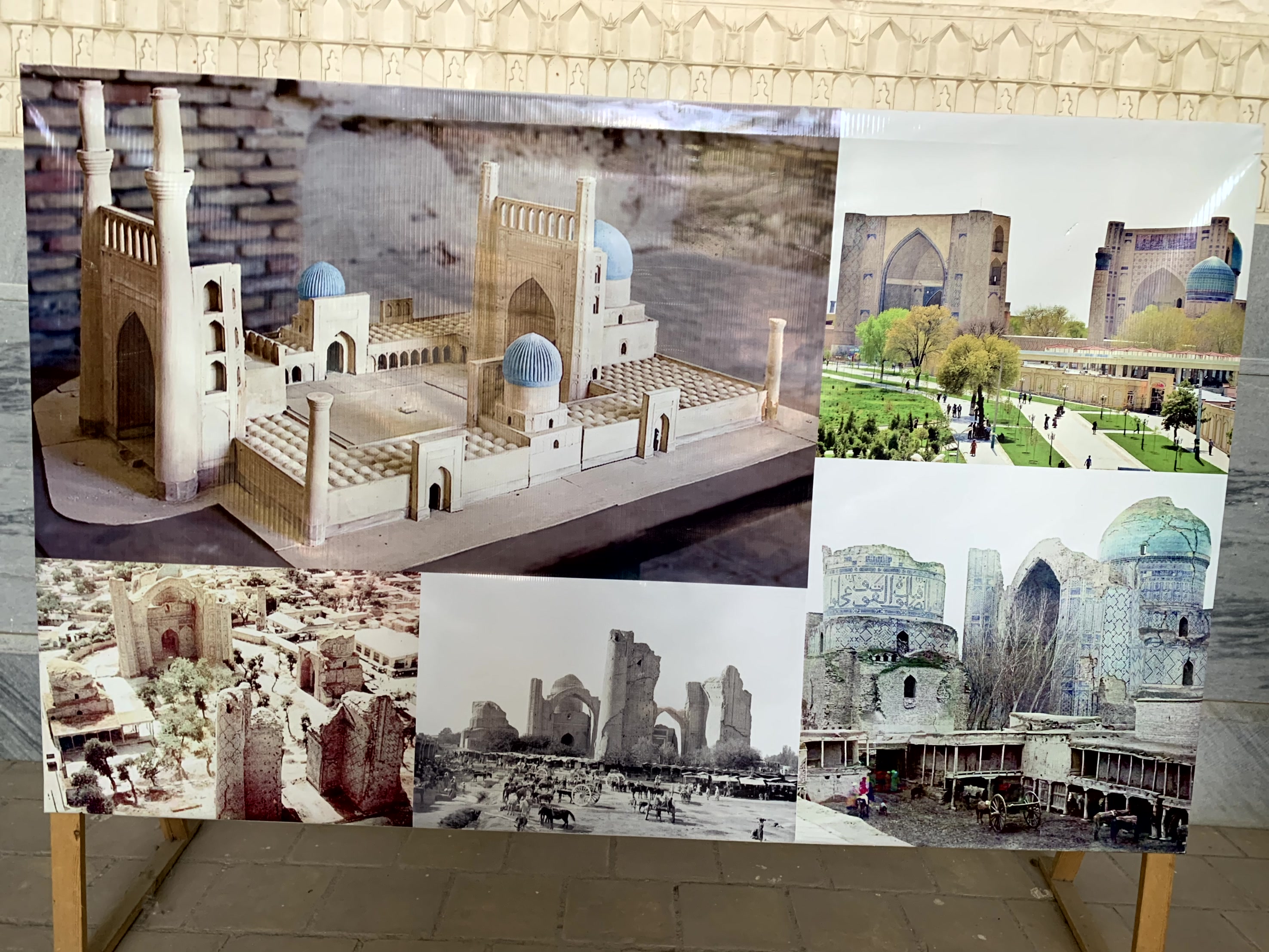

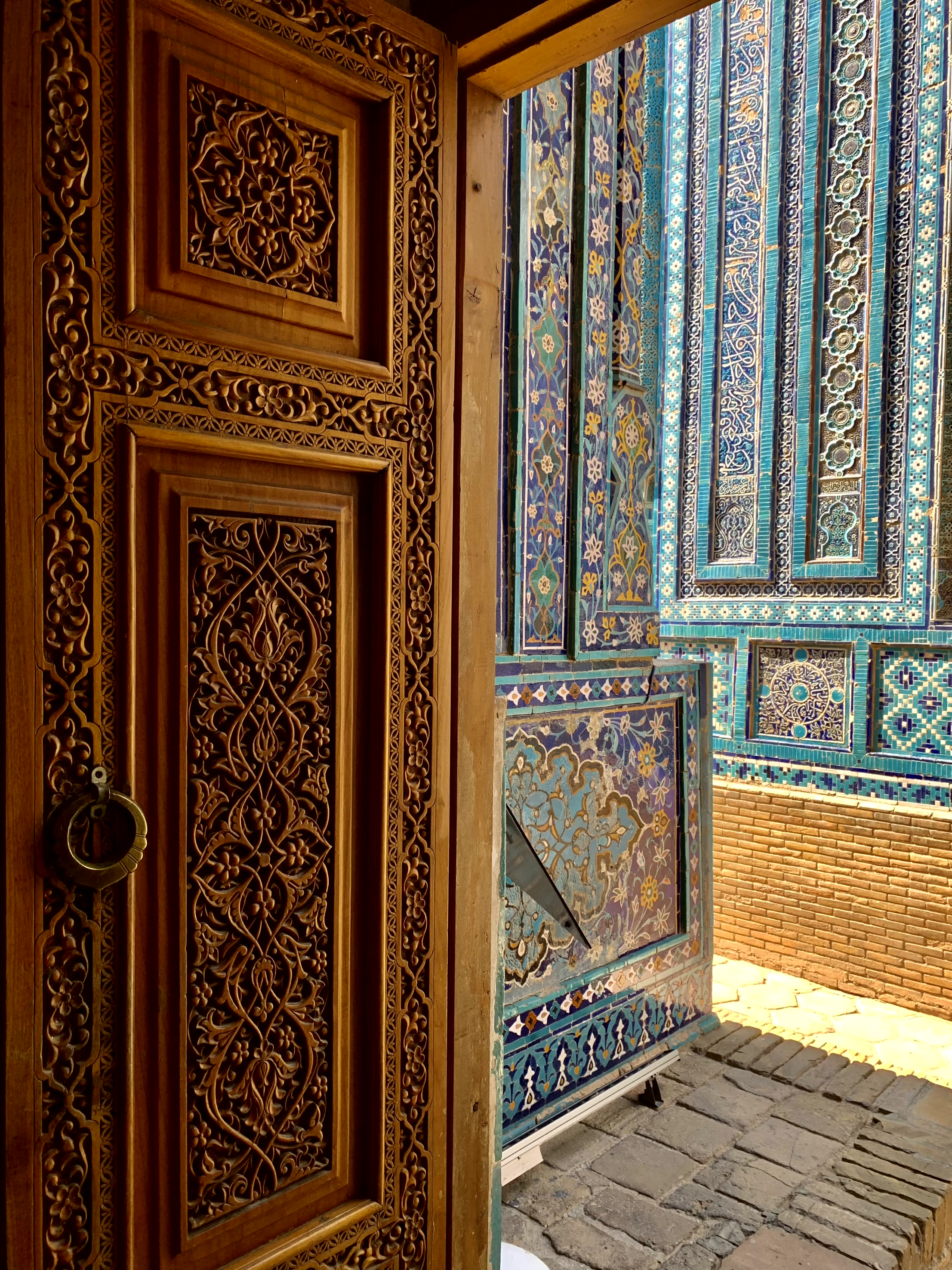

Bukhara dates back 2,500 years. After independence, when the second Uzbek president came to power in 2016, the city was off on the tourist trail. Then, airlines came and credit cards began to be accepted. Its centre is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site listed as ‘a well-preserved example of a 10th to 17th-century Islamic city in Central Asia’. Bukhara is an oasis city that has been destroyed and rebuilt many times. The most notable of these periodic phoenix-like moments were in the 1920s, when Russian shells and an aircraft wreaked havoc on the city and in the 1220s when Ghengis Kahn raised the city to the ground. Water channels had supplied the city since early times and the Russian bombs damaged them ushering in a cholera pandemic that led to the water tower being built and the redundancy of the water-carriers. Sogdians, Persians, Greeks all had a turn in the city. Even Emir Timur popped in. When Ghengis Kahn stopped by, by the time he left only three buildings were left standing – no older buildings survive in Bukhara today. One was the mausoleum of Ismail Samani, whose enlightened rule encouraged education and he was so popular that the local population buried his mausoleum to save it from the Monguls when Ghenghis Kahn was laying siege to the city. The second is the eleventh-century Magok-i-Attari Mosque (now a carpet museum and built on the site of an ancient Zoroastrian temple) which probably survived the flames because it was set in open ground. The last survivor is the Kalon Minaret. The story goes than when Ghengis Kahn rode up to this impressive structure, his helmet fell off. He dismounted and knelt down on one knee to pick it up. As he arose, he looked up at the minaret and noted that this was the first time he had knelt before a building, so spared it. The Kalon Mosque was not so lucky. But this was still rebuilt with amazing knowledge and skill: the wooden pillars stand on plinths and hold up the entranceway. Between them, the builders put camel’s hair, which makes them flexible enough to withstand earthquakes.

The 47 metre tall Kalon Minaret was built in 1127 by Arslan Kahn and its foundations go down a further 10 metres. It would have been one of the tallest buildings in Asia. Once the foundations were completed, the ruler’s architect (Usto Bako) simply disappeared and was not seen or heard of again for the next two years. When asked what he was playing at, the architect explained that the foundations needed to settle for this time and if he’d hung around, he knew that his ruler would hassle him to get on with the work. He obviously did a good job, using local stone and mixing mortar with camel’s milk, egg yolk and honey which was the right thing to do: the minaret has stood tall through nearly nine hundred years of earthquakes, sieges and invading armies. Bako would only work in July and August, the hottest months, and would only add two courses of bricks at a time, leaving them to settle overnight. He had his grave built at the tip of the midsummer shadow from the minaret so that if it ever fell, then it would disturb his rest.

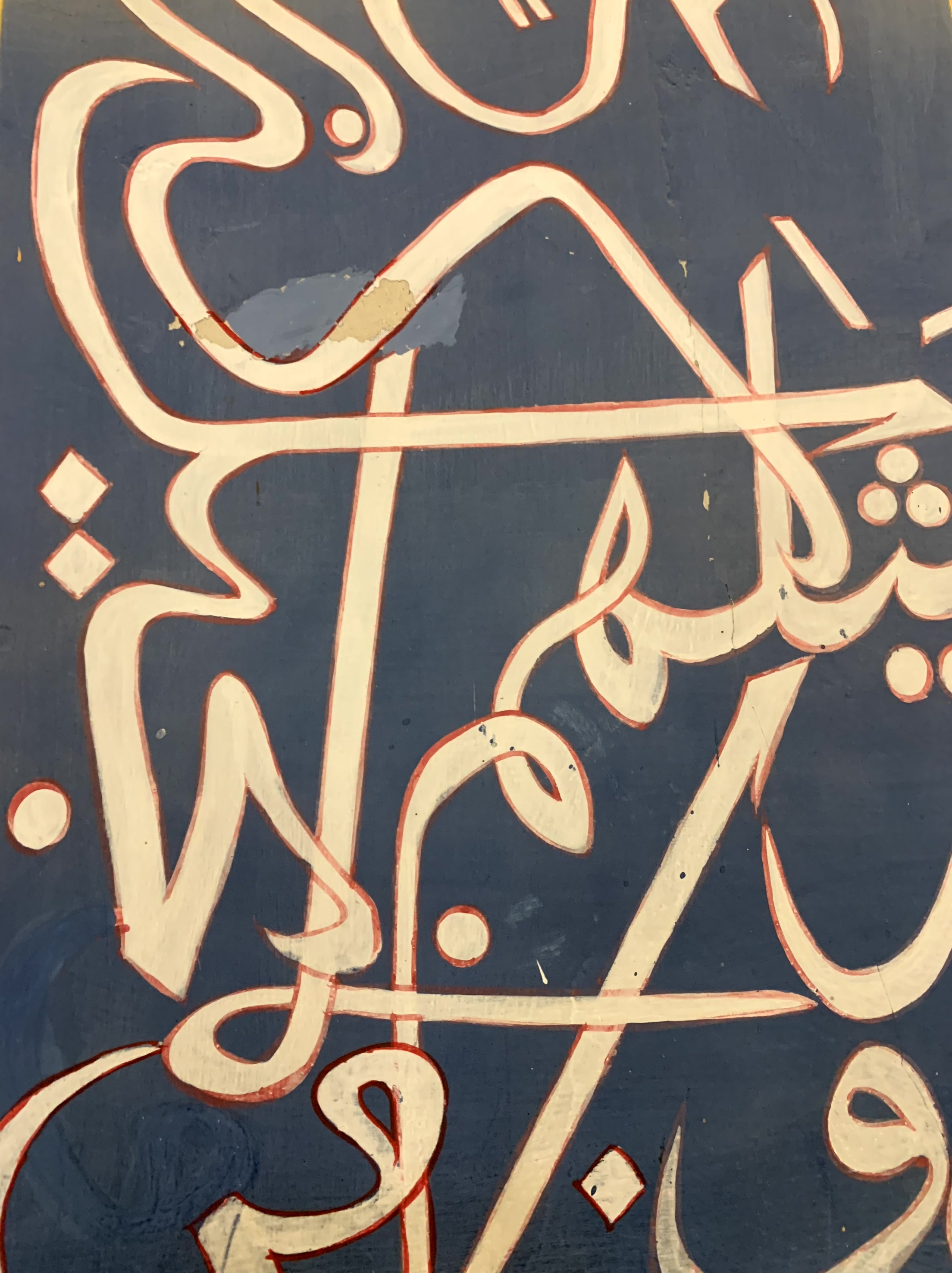

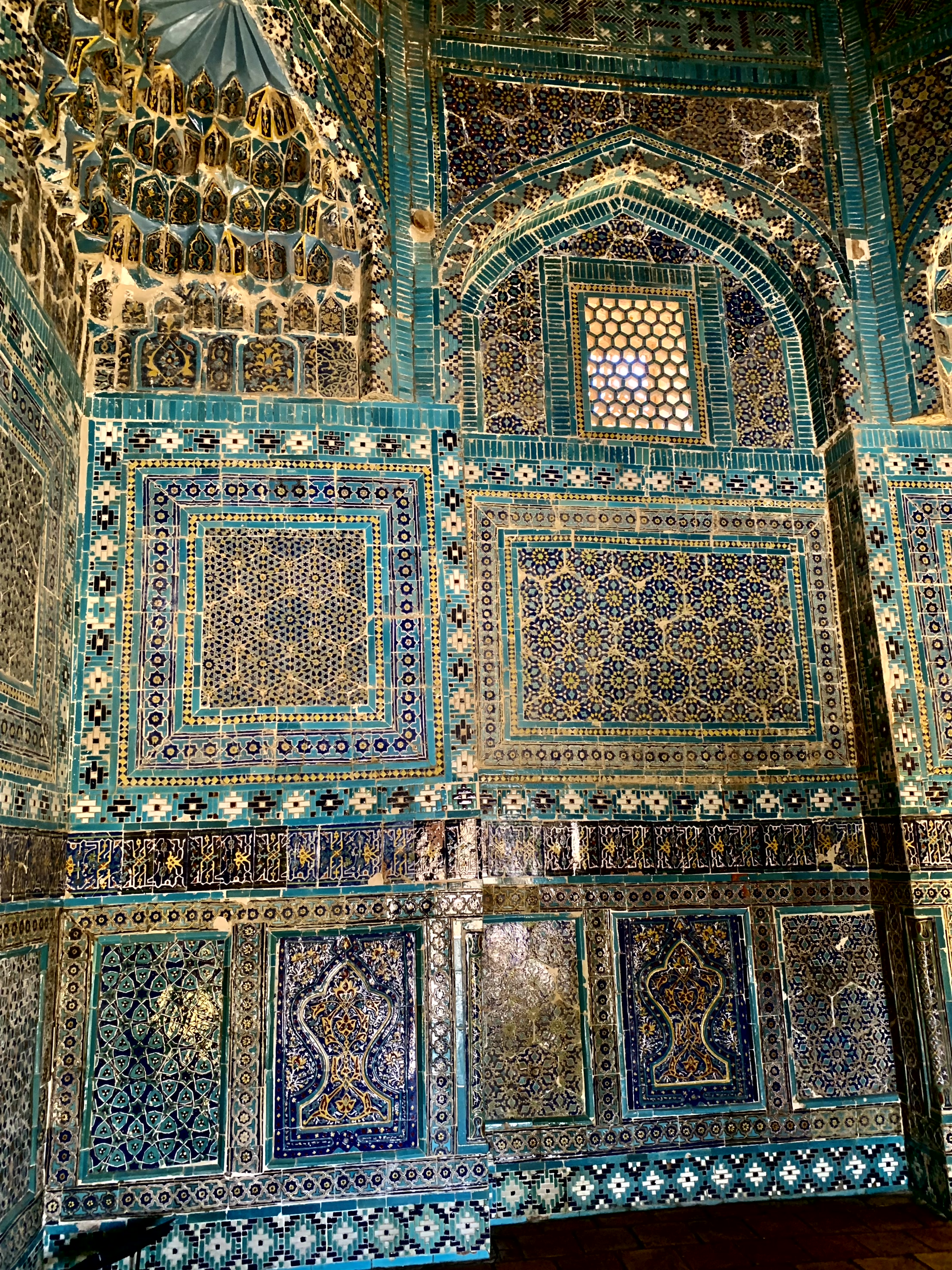

The Mir-i-Arab Madrasa is one of only two still in use as a centre of learning in the country. It’s the Oxford University of Uzbekistan, where boys come to study science, the history of the Qu’ran and where they learn about the Prophet (PBUH) before becoming imams. I can see some of the future imams through the grille, the academic elite, strolling around the courtyard and playing table tennis in the shade. When it was built, the very best of craftsmen were hired from as far away as China and India. This accounts for depictions of dragons and phoenixes (an ancient Zoroastrian symbol and the emblem now of Uzbekistan). I had always thought that in Islam people did not depict living creatures but for a short period in the 17th century this was permitted. Half of the frontage is decorated intricately, the other half was left plain in the hope that in the future, more skilled artists would come along and finish it. One side of the building is still left plain right up to this very day, which must say something of the original workers.

I only had two nights in Bukhara so I spent two half-days solo-wandering with a guidebook and hired a guide for a day’s tour to get some more background. Faïs turned out to be a fabulous guide and arrived with a folder full of documents of historical and cultural information so that he didn’t misrepresent or forget anything interesting. A very personable and diligent guide. Consequently, I learned a lot about Bukhara, and my questions were answered admirably and accurately.

‘Chorsu’ is a word which means crossroads and here in Bukhara, this is where specialised traders set up shop in covered marketplaces. So, one is the moneychangers chorsu, another sells spices, and another hats and so on. The hats are in styles that show which tribe you are from, how old you are or whether you are married… There is one stall selling what look like sewing bobbins, but I learnt that they are for imprinting the sign of the bakery into loves of bread.

Armed with my trusty Lonely Planet guidebook and information I found online, I made for the unusual top site recommended. This was to sit on the Chashmai Mirob Cafe terrace and watch the sun go down over the Kalon Minaret. I tried to walk there but got hopelessly lost so had to flag down a taxi. The man had no idea what I was talking about when I asked for the cafe but I managed to get a deal to the minaret and he didn’t overcharge me. Now there’s a first. And it was worth it. I got chatting with a Russian mother of about my age and her daughter there, which I enjoyed immensely because when I told them I’d been walking up to 15km a day on my travels in Uzbekistan, the daughter told me that this was the reason I looked so good for my 61 years. I liked them.

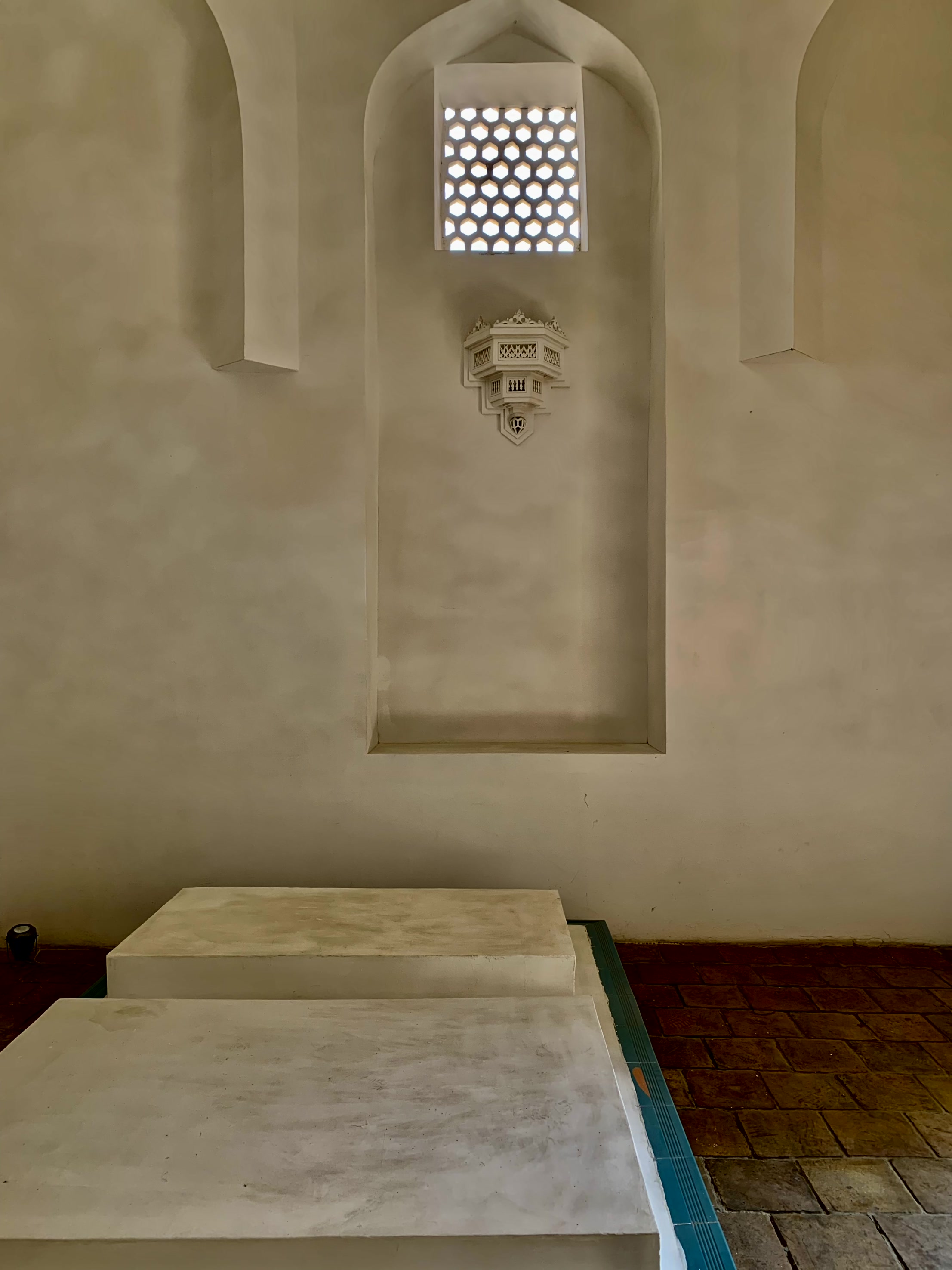

Up on a hill by the Khalon Minaret and mosque is the Ark. This is where the Emir lived, or what is left of his impressive palace complex. Most of it was smashed to smithereens by Russian bombing. Under the ramparts, is the old and infamous Zindan Prison. In 1842, Colonel Charles Stoddart and Captain Arthur Conolly were released from here and told to dig their own graves in the square under the entrance to the Ark, where the Emir had a good view of proceedings from the balcony above. They were then beheaded. The problem was that Stoddart had come here to appease the Emir after Britain had invaded Afghanistan and did not want the Bukharans siding with the Russians; he arrived with no gifts and did not dismount when approaching the Ark. The Emir considered himself an equal of Queen Victoria and was also disappointed that Stoddart had come with a letter not from her, but from the governor-general of India. In fact, he was so disappointed that he had him thrown into the ‘bug pit’. He remained here for three years and was joined by Connolly in 1841 when he had come to try and get him out, by which time Stoddart had converted to Islam having being told to do so by his jailor under the threat of beheading if he didn’t. The ‘bug pit’ was reserved for those who had really upset the Emir and amounted to a death sentence (the regular throwing of rats, scorpions and other biting or stinging nasties into the pit notwithstanding). You can visit the jailhouse today, with its three cells: one for people who had committed crimes against other citizens; another for those who had wronged the state authorities and then the notorious ‘bug pit’ for those who had no hope of ever getting out. When the Emir received no reply to a letter he had sent to Queen Victoria, he had both men killed. The British Government let the matter drop, but friends and relatives of Stoddart and Connolly raised money to send their own emissary to Bukhara to verify their fate, a clergyman called Joseph Wolff. Wolff only escaped certain death and a stay in the ‘bug pit’ because he dressed in full ecclesiastical garb and the Emir found him hilarious and somewhat ridiculous and sent him away with his head still attached to the rest of him.

I learned from Faïs that the pond just next to the hotel, the Labi Howz, dates back to the 16th century. A famous film from 1943 was shot here chronicling the adventures of Nusradin, a sort of Uzbek Robin Hood who travelled on a donkey. There is a statue of him next to the pool, riding his donkey. One story is that once he came across a fat, rich man who was drowning in such a pond. Nobody could reach him with ropes so Nasradin showed him a gold coin and said, “Come, and I will give you this gold coin,” and low and behold, the fat, rich man got himself out and was rewarded with the coin. Another tale recounts how Nasradin went to the Emir one day and asked for one bag of gold in return for his clever donkey who after twenty years would actually be able to read. People said that he would be in trouble. “After twenty years,” Nasradin told them, “neither me, nor the donkey, nor the Emir will be alive,” and off he went with his bag of gold.

People bring prospective brides to the Labi Howz, if the parents of the prospective bride and groom agree, unchaperoned to meet and size each other up. It is a popular place to have wedding snaps taken and is known locally as ‘Love Square’ and Faïs had come here with his wife before they were married. The 5m deep pond is fed by one of the canals built from the river and it is surrounded by ancient mulberry trees which help to keep the water clean and whose roots support the brick walls it is made of.

There is a story of one Nadir Divan Begi, who had financed the building of the pool and surrounding buildings and one day decided to get married, presenting a pair of earrings as a wedding present to his bride. The bride got offended by the fact that only earrings were offered. She was sure that the groom was from a wealthy family and could easily afford to present more valuable a present.

After a few years, he began construction of the Lyabi Howz complex and his wife became quite indignant and told him that it was not fair to spend such a huge amount of money on the construction when she was only presented with earrings as a wedding gift. Then, Nadir Divan Begi asked her wife to check her jewelry box and she found that one earring was missing. She cried ” I’ve been robbed!”, but then her husband explained that the entire complex was going to be built on the value of the one earring he had taken back. To build this, he had had to ask a Jewish widow to move out so he could demolish her home. It took a lot of persuading this Esther and she held out until a deal was agreed that he would build a synagogue in return so that Jewish people would no longer have to go to a mosque to worship, which is the four-hundred-year-old synagogue we see today. Also today, Jewish and Muslim worshippers co-exist in mutual respect and harmony in Bukhara. Now, there’s a thought. The Jewish community numbers only 100 to 150 Jews nowadays, most having emigrated after the Russians left, but probably no more than five families who keep kosher and follow Jewish traditions. The city has only one elderly rabbi.

Faïs took me around the Kukeldash Madrasa, built in 1568 and by ‘took me around’, I mean that we explored the bits tourists would not necessarily find their way to: the upstairs living quarters for example, reached via a narrow stairway behind one of the inevitable stall-holders downstairs. At one time, it was the largest madrasa in central Asia. This was a science academy open only to males (like most) and entry was by exam. It was funded by its own caravanserai. From the age of about fourteen or fifteen, rookie students arrived with two bags of edible treats, one for the student and one for the teachers. They said that the bones belonged to the parents, but the meat to the madrasa: in other words, licence to beat as necessary. The doorways are low, to save wood and also so you had to bow before entering and learn humility. The architecture is designed to be cool in summer and warm in winter. Cooking coals were put on floor slabs, which in turn provided heating for the building. The living quarters upstairs had handy storage shelves and layers of peeling paint telling the stories of centuries of use, including graffiti from the 1920s onwards when the madrasa was shut down so the building could be used as barracks by the Russian military.

The crème-de-la-crème of Asia’s artists and architects, bloodthirsty invaders and rulers, scholars and philosophers, a Russian bomber and Silk Road travellers have all left their mark on Bukhara over the centuries. The stories of these adventurers ooze from the very bricks of the stunning madrasas, the pleasant shady pools, the beautiful mosques, caravanserais and minarets we see here today. Now that deserves a visit, wouldn’t you say?