Our first stop on the road trip is Karaman, where we find ourselves on the ninth floor of a rather smart hotel with a spa (which didn’t work) and a swimming pool in the basement. It sticks out as one of only a handful of high-rise buildings in Karaman. We have a panoramic view of the city from our room and manage to work out the etiquette of roundabouts from up here. We can clearly see that cars on the roundabouts are giving way to cars coming on. So that was a useful tip.

The restaurant is on the tenth floor. A very smartly besuited Maître d’ is obviously the one in charge around here. At his elbow trots a remarkably young-looking waitress, following his every move like some starstruck, puppy-eyed disciple. She looked terrified. He marched up to our table and declared that this girl had just started today and wanted to learn English, so he was showing her how it was done. He has a small greying beard and what appears to be a minimally and badly-disguised jet-black toupé… how can I say it… let’s go with ‘perched’ on the top of his head. I wanted to yank it off, I can’t deny it, if only to make that poor, petrified child crack a smile and relax a bit. He tells us that he is a retired firefighter, recently returned from the earthquake zone where he volunteered his services without asking for any pay. Then he asked us what we did for a living.

Back on the road the next morning, we make a small detour to visit Manazan Caves. Dating back to the Byzantine era, the 6th to 7th centuries, these caves were once homes, temples and store houses. They are still used for storing grains by the inhabitants of Taşkale village just up the road, where we visited the newer 800-year-old granaries, also carved into a limestone cliff face, and secured with juniper wood doors. They are about 50cm across, and the granary caves provide the perfect temperature and humidity to store grains for many years. Some of them are quite high up and are accessed using foot and hand-hole niches in the cliff. Some are even used as living spaces.

In Taşkale, a man approaches us as we are looking up at the doors in the rock.

“Do you remember me? I am the waiter in the hotel in Karaman.” Well, blow me down with a feather! If it isn’t wiggy, but this time dressed more like a shepherd than a Maître d’. But he does have his firefighter’s jacket with him, which is perfect for the snowy winters here he assures us.

“This is my shop. Can I offer you some çay?” he asks, unlocking the padlock to the low stone building behind him. He also has a caravan opposite, which he runs as a snack bar for when tourists visit. In addition, Hassan keeps bees and hopes to develop his business into an international carpet emporium online and to travel the world. But he needs to get electricity to his shop first and that costs money he hasn’t got. He travels for a 100km round trip on his motorbike two days a week to work in the hotel, where he is also the Head of Security. All for TL50 (about £20) a session. He finished at 2 a.m. last night. His final duty of the shift was to search the bags and persons of the restaurant/bar staff for pilfered cutlery or items of unused food. They even try to deposit these in bins to collect later but he is wise to that. His boss, however, allows him to take the unused bread to feed to his dogs he tells us, tossing a few tasty, stale rolls out of the door from the large paper sack he has in his shop.

Hassan is an interesting guy to chat with. He started learning English at the age of 12 when he ran his own shoeshine ‘business’ outside the American airbase in Adana. This is how he taught himself the language, asking the airbase staff, “What is this?” and writing the words down on his hand to practise later until he remembered them. It could have been that he just wanted to practise his English or maybe it was because we just got along swimmingly and enjoyed a conversation, but he didn’t even try to sell us any carpets (although I did buy a little trinket from him and gave him about four times the marked price for it). He tells us about the quality of his thick rugs: carpets that you could sleep on in comfort. And then the thinner ones that would give you back ache if you tried this. Finally, the scratchy, course ones, designed to keep snakes and scorpions out. Hassan’s grandfather also told him that snakes and scorpions hate the colour blue. In the daylight, I think I may have misjudged Hassan. The toupé could actually be low-quality hair-dye. It doesn’t matter really. He seemed like a nice enough chap to me. Hassan tells us that sometimes guests in the hotel behave badly. Like the drunk woman a couple of weeks ago who offered him $100 to give her some very personal services. After looking her up and down, he asked for $200. “No!” she told him, looking him up and down, “300!” And so the deal was struck and he continued by giving us far more detail than we would have liked, involving some punching out of the cheek with the tongue in rhythmic synchronicity with accompanying fist gestures. “It is the only time I ever cheated on my wife,” Hassan assures us, putting his hand on his heart for emphasis.

“Hassan”, (Maître d’, Head of Security, Firefighter, Snack Bar Owner, Carpet Salesman, Shopkeeper, Beekeeper, Farmer, Prostitute and Pimp — he also rented out his granary in the cliff and his shop for amorous youngsters)…” I hope you bought your wife a really nice present with that $300,” I tell him. Hassan seems to like this idea. But from the look on his face, I figured he’d already spent this money on something else.

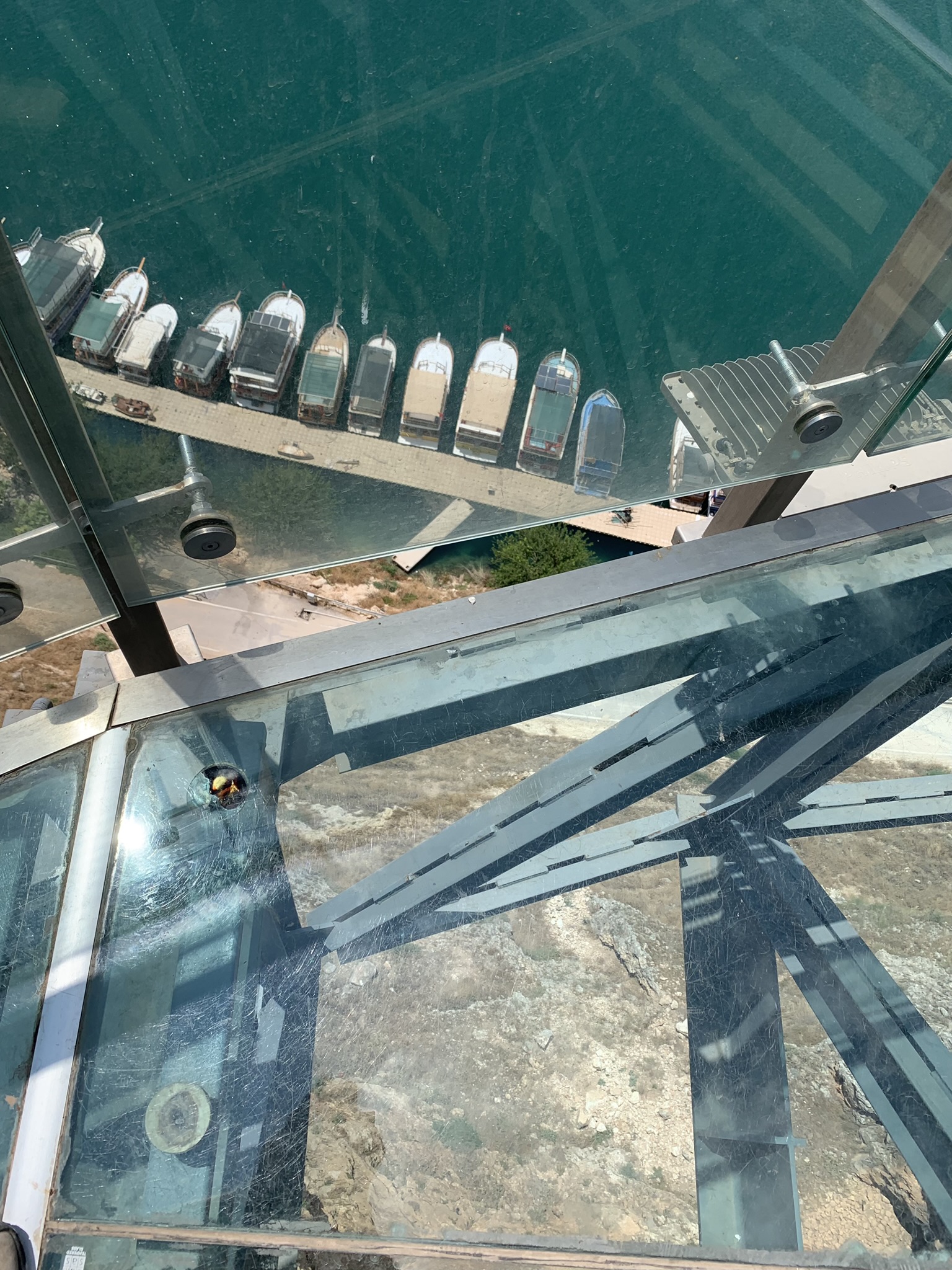

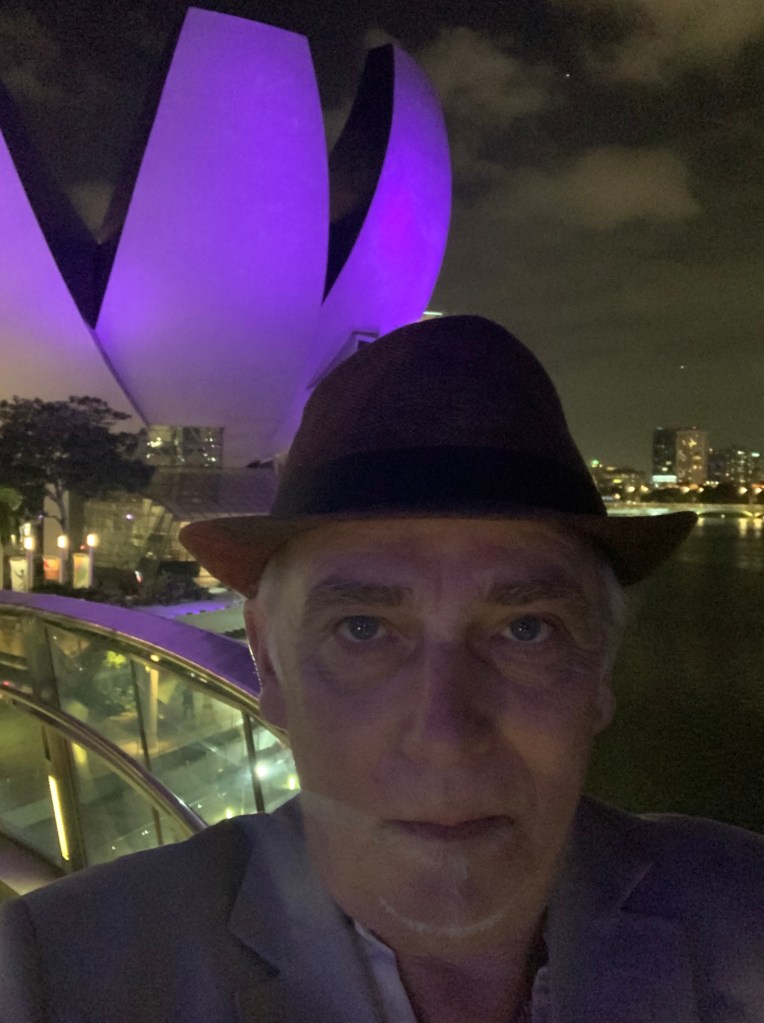

We make it to Gaziantep that evening, a spit away from our goal of Şanlıurfa. En route is our final sight-stop at Rumkale Terrace overlooking a stunning horseshoe bend on the sublime river Euphrates. There are boats moored by a floating pier, but all the stalls and cafes are closed because part of the jetty has crumbled away into the river as a result of the earthquake. It has the atmosphere of a ghost-town. Sticking out from the high cliff, is a glass-floored terrace. Up there is a café and it’s a great place to sit and people-watch as new arrivals show their unique reactions to a quite surreal experience. You look down between your feet to the jetty and river way, way below through the glass floor. And if you are afraid of heights, like I am, then you have to overcome this to get to the waist-high glass wall at the end where the perfect photo is to be had. Some people clung to the glass wall at the edge as they stepped timidly towards the far end. I tried this, but it didn’t work for me. In the end, I favoured looking straight towards the mountains and ruined castle on the opposite bank and walking directly ahead in quite a fierce way, ignoring the whole thing until I got to where I wanted to be. Then I tried to look relaxed for Stu to take a photo while I virtually dented the steel rail in a vice-like, one-handed grip.

I get chatting to the guy in the café who asks where we are from. “England,” I tell him.

“Where in England?”

“Oh, the southwest.”

“Do you know cushty?” he asks. I think that maybe this could be some place in Lincolnshire, or Cheshire, or Shropshire that I would never have heard of. “Cushty?”

“Yes. In London. Cushty.” And then the penny drops. Orhan is talking cockney.

“How on earth did you learn cockney?”

“I worked in Greece as chef in a hotel for Thompson Holidays and these people from London, they told me this.”

“Amazing,” I smile. “Are you serving food today, Orhan?”

“Yes,” he replies. “We have chicken or troite.”

“Troite?”

“Yes, troite. You know. Fish”

“Ah, trout!”

“Yes, troite.”

“Orhan, is the… er… ‘troite’ cushty?”

“Yes, yes, it is cushty troite,” he laughs.

“Well I’ll have a cushty troite then, please.”

“And I’ll have the cushty troite as well,” concurs Stu.

And very nice it was too!

Read Part 3 of the quest to Göbekli Tepe here.